The Mediterranean basin always encouraged mobility of people living around it like “ants or frogs around a pond”, ὥσπερ περὶ τέλμα μύρμηκας ἢ βατράχους περὶ τὴν θάλατταν οἰκοῦντας (Plato, Phaedo 109 β). The Greek presence on the Italian peninsula is attested as early as the Mycenean period and reached its peak with the Greek colonization of the 8th-6th c. BC. Cultural and emotional links between the Greek colonists of Magna Graecia and metropolitan Greece remained strong and intense, as is evident from their victories in panhellenic athletic contests, their numerous votive offerings in sanctuaries, and their presence in the most renowned oracles, such as those of Delphi or Dodona. However, economic activities in the East on their part were limited and on the part of the Romans are not attested before the 3rd c. BC. It was only during the 3rd c. BC when internal evolutions on a political, social and economic level in Rome encouraged an economic outreach of Romans and Italians towards the East (Italians had not yet received Roman citizenship as a whole; it was granted to those who were enrolled in the communities of the allies of the Romans in 89 BC). The earliest historical reference to Italian merchant activity in the eastern Mediterranean is in Polybius (2.8,1) who mentions that the Roman involvement in the Illyrian War (228/7 BC) was aimed at wiping out Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic Sea since they robbed and killed Italian traders who sailed towards the East: Οἱ δ’ Ἰλλυριοὶ καὶ κατὰ τοὺς ἀνωτέρω μὲν χρόνους συνεχῶς ἠδίκουν τοὺς πλοϊζομένους ἀπ’ Ἰταλίας: καθ’ οὓς δὲ καιροὺς τὴν Φοινίκην διέτριβον, καὶ πλείους ἀπὸ τοῦ στόλου χωριζόμενοι πολλοὺς τῶν Ἰταλικῶν ἐμπόρων ἐσθ’ οὓς μὲν ἐσύλησαν, οὓς δ’ ἀπέσφαξαν, οὐκ ὀλίγους δὲ καὶ ζωγρίᾳ τῶν ἁλισκομένων ἀνῆγον. This passage shows that in the second half of the 3rd c. BC the Italian presence in the eastern Mediterranean was already frequent enough and that their navigation and economic activities were protected by Rome.

This presence increased in time and ranged from mobility to migration, from temporary to permanent settlement, from commercial transactions to “investments”, and from cultural interaction to acculturation. The motivation of private westerners who –with their own initiative and not on the basis of a planning or an order of the central Roman government– moved from the west to the east from the 3rd c. BC onwards, could vary (pilgrimage, cultural tourism, education in Athens, exile), but above all it was their search for profit. The activities which they carried out and the range of their economic success differed from place to place depending on local natural resources, geographic location and the general prevailing circumstances. Agents of large business interests, ready to invest in various sectors of economy, and people of a low social profile, who attempted to pursue a better future outside of Italy, aimed at the profit opportunities which were offered in Greek land where –with few exceptions– the majority of productive forces were exhausted by the long-lasting preceding period of wars, which led to the drying up of economic and human resources.

The human capital that moved from Italy to the East, should have been enormous, if one takes into account e.g. the figures of Ephesian Vesper’s victims (88 BC, the King of Pontus Mithridates VI ordered the slaughter of Italian and Roman residents in towns of Asia Minor and on Delos). The numbers range according to various ancient writers (Valerius Maximus 9.2,3; Memno 22.9; Plutarch, Sulla 24.4) from 80,000 to 150,000 victims, but offer an idea of the multitude of Italian residents in Greek poleis of the east. The migration wave increased again after Sulla’s victory over Mithridates, so that Caesar (Suetonius, Caesar 42.1) was pushed to take measures in order to limit it.

The presence and activity of these people in the East are imprinted on numerous written and material sources.

The aim of this project is to systematize for the first time numerous primary sources of written evidence which attest to the temporary or permanent presence of Italians and Romans in the poleis of the Greek mainland and the adjacent islands. To that end, dozens of literary sources and thousands of epigraphic texts are being analyzed. Every individual who is mentioned in written sources and can be identified with certainty or with good reasons as Roman or of Italian origin is registered in a prosopographic data base which is the backbone of this project. Thus, it will offer a detailed record of Romans and Italians who are known to have moved or migrated to Greece, providing all sources where they are attested, as well as comments of their activity and life and additional bibliography.

This pool of evidence can feed various further synthetic studies. Numerous archaeological finds that are evaluated as important for the research and are occasionally mentioned in the database, are to be combined with prosopographical analysis in order to contribute to an innovative comprehensive examination of the issue including dimensions which were heretofore totally or partially neglected or ignored.

The importance of this research lies in the significance of the role of Italians and Romans in social and economic life, even in the shaping of a new physiognomy of the poleis of Greek East, given the mutual impact both on various aspects of life of the host communities and on the social, cultural and economic status of the foreign residents. This manpower rushed to the East full of enthusiasm for profit opportunities and partially relied on the relative security provided by Rome’s support and Roman citizen’s identity (a right that was expanded to Rome’s allies in Italy in 89 BC). This foreign social element integrated into local societies, exploited natural resources, gave a new impulse to economic life, frequently invested capital in local economies and evolved to a dynamic part of social life, negotiating its identity and finally acculturated and assimilated into local communities.

——————-

Warm thanks:

– to Dr. Georgia Pliakou, Head of the Department of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and Museums, Ephorate of Antiquities of Thesprotia, for permission to use photos of an amphora found at Dymokastron, which bears a Latin stamp and was published in the Proceedings of the 4th IARPotHP Conference, Manufacturers and Markets: The contributions of Hellenistic pottery to economies large and small (November 11-14, 2019).

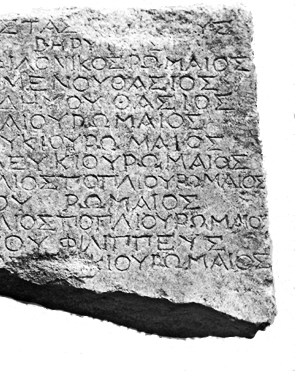

– to Prof. Cédric Brélaz, Université de Fribourg, Institut du monde antique et byzantin, for permission to use a photo of an inscription from Philippi, which was published by Cédric Brélaz and Angelos Zannis, « Inscriptions hellénistique de Philippes mentionnant des citoyens romains », Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 2014, 1493-1501 (copyright of the picture: École française d’Athènes, cliché L. 4612, 30a).

Contributors

Sub-project Supervisor:Zoumpaki Sofia, Research Director IHR/NHRFΕ

Research Associate (adjunct): Lina Mendoni, Senior Researcher IHR/NHRFΣ

and Konstantinos Andreas Liapatis, Master Student of History